“Doc, you called just in time. I was thinkin of doing bad things to myself, if you know what I mean. You reminded me of all the good stuff I got, my wife and kids, the boat Junior and I share out on the river. All my tools. Even the damn dogs. Christ, Doc, you near saved my life.”

Later I told Michael I knew only too well those same feelings. Some thoughts help, some don’t. Anyway, things lightened up, another year rolled round and we agreed I’d come to Michigan in August.

Mike works the graveyard shift so his stepson Jerry gave me a ride from Metro Airport. Jerry is seventeen, a good clean kid, unlike his two older brothers, who are skinheads, dope fiends and losers. We stopped at a Big Boys, I scarfed up on the salad bar and Jerry had spicy buffalo wings. J enny, his cute, blonde haired, blue eyed sweetheart, didn’t eat much but warmed up to the general conversation about country music, work and Florida - which is where Jerry would like to take her since not much happens in Monroe.

Then we drove to Mikes’ place. I met Kathy, Mike’s wife, and Cody, Mike’s scruffy little dog, and Jerry left to drive Jenny home, so Kathy and I had time to talk before Mike got in from An Arbor.

Kathy said, “Doc, I just don’t understand why Mike don’t talk to me like he does you. He knows it makes me angry sometimes, the way he’ll start to talk about the war, then just shut me out. ‘You don’t understand’ he says, then he’ll walk away. “Though sometimes Michael will holler at me an I’ll holler back, and then we’s to fighting. C an you figure that out, Doc? cause I sure can’t. It makes me hurt when I see him like that you know what I mean?”

I understood but wondered what next to say. During last year’s visit Mike and me had kept pretty much to ourselves, leaving Kathy out. “Well, it might go something like this,” I said. “He talks to me because I was the medic. He feels safe with that. If Mike opens up to you he might be thinking he’ll break down, lose it, maybe cry, maybe explode. A lot of vets are like that, Kathy. They’ll let you get only so close, then you got to back off... you got to, because then you’re playing with fire, and that fire is a powerful, dangerous thing; an inferno of rage, sorrow, terror and fear. You mean well, Kathy, but Mike’s in pain when you move in like that, so he says something or gets high strung, but he’s really screaming and crying at the same time. It’s not your fault; that’s just the way it is.”

I could have said more, but some things just don’t translate. Kathy said, “Damn, Doc, I never thought about it like that. I want to show Michael I care, but not get him all upset like you’re saying. Am I making sense?”

“Yeah,” I said, “ You’re making sense. Tell you what. This time let’s do more stuff together and see how it works, OK?”

Kathy said, “Sounds good to me, Doc. An you know, Michael’s so pleased you come to see us.”

Mike got home after midnight and we sat in the garage, his ‘bunker,’ he calls it, till 4am looking at war flicks I’d brought. He didn’t say much at first but the light slowly came into his eyes.

“Goddamn, that’s Carrot Top, don’t he look mean!” he said. “Shit! Damn! I know this guy, too! T ried to put me out in the bush when I was short. Saw me smoking weed one time, told me to put it out, I just turned my back on him. Next thing I knew he’s got me back on patrols. Cocksucker! But I fixed his sorry ass. S poke to the Captain and we turned things right round. Oh yes we did.”

I looked at the photograph. A handsome confident bare-chested black man with a pencil thin mustache stared back at me.

“Jesus Christ, Mike, that’s First Sgt. Keen. He tried to screw you like that? Maybe he thought you were being racist or something. You know, white boy saying ‘fuck you’ to a black non com.”

Mike said, “You might have something there, Doc,” and slowly turned the page. He’d lost most of his pictures and some of mine were pretty good, and he was remembering things I’d long forgotten. From time to time we choked up, even with Kathy there.

“Looky here, there’s the Bopper, and Jim Lamb, and oh shit, that’s Jim Dumb the Kit Carson Scout, and that there’s that fuckin papasan, working for the NVA. Holy Shit, it’s Snake! Fuckin’ Snake! He was a righteous dude. And Indian Joe, fuckin’ Indian Joe. Oh Jesus, that’s Ernie the FNG! What was his last name? Kovel? That’s it! Kovel! The one who got tapes from his Dad, train sounds, he played them train sounds in the jungle, remember that, Doc?”

I said, “Yeah.”

We let it go that in a fire fight Ernie the FNG had shot the man in front of him. Let it go.

Kathy said, “That FNG means a new guy, right Michael?”

Mike said, “Yeah, that’s a new guy alright.”

She smiled with self-satisfaction.

Then Mike recalled how we’d sneak over to an abandoned ville outside LZ Compton and fire M-79 rounds into an old French water tower.

“We’d go there with the thumper and blast that thing,” he said. “I think you nailed it a few times, Doc. ‘Member how much ammo we took down there? then got hit one night and the LT got so pissed cause we’d shot all the 79 rounds up? Remember that shit, man? Oh Shit!”

Kathy said, “The LT was you’re platoon leader, and you called him Carrot Top ‘cause he had red hair, ain’t that right?”

Mike and me both said “Roger that.”

With each page he’d recall names, places, events from our youth.

“That patrol off Compton when the mamasan, her kid and the old man popped out from behind a tree and we nearly wasted ‘em.”

I nodded my head but Mike was already talking about a patrol I’d missed. They’d reconned an empty ville and searched the hut of the head honcho, took down a painting, then put it back in a different spot just to freak him out.

“And then we come across them dink mouse traps made of bamboo, had them little nooses to strangle the mouse once it grabbed the bait. You don’t remember that, Doc? An we left the place same as we found it, ‘cept for some bows and arrows and pottery we took; shit like that.”

We talked about the night in Cambodia when LZ Ranch got overrun.

Mike said, “The fuckin’ gooks was inside the wire and Six , he says to me, ‘Let’s go,’ so we went after’em, just him and me; he liked that shit, man. And we was outside the berm, outside the fuckin’ berm, an I seen one crawling thru the concertina; seen’er and greased her good! Oh shit! You ‘member that night, Doc? A ll night, all fuckin’ night. An I seen this one dink gotta bag with two little holes that was glowing and I wasted that fucker too, I shot that cocksucker good! Christ, yeah! You remember, Doc?” I said, “They blew two gun pits and we took twenty-five wounded and five KIA, at least that’s what’s in the After Action reports. Snoopy dropped basketball lumes that swayed back and forth, Artillery popped a red flare, yelled fire in the hole. Everyone ducked. Then the 155 shot direct fire, and Bo Dop dropped 175 in the wood line.”

“Yeah!” said Mike, “That was some heavy shit, Doc. Heavy shit. And you was helping out with the casualties wasn’t you? You and the other medics. Them dinks had our number that time. Jesus H. Christ.”

I said, “Michael, why don’t you keep the flicks for a while?”

“Yeah, Doc. So’s I can look at them at my leisure. That’s a good idea. Thank you much.”

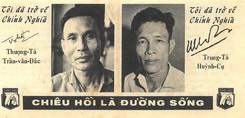

Just before turning in I showed Mike and Kathy the Chieu Hoi leaflets I’d held

onto to all these years.

Just before turning in I showed Mike and Kathy the Chieu Hoi leaflets I’d held

onto to all these years. Mike put his arm around Kathy. “You see, they dropped these here from special copters for the dinks. It’s like propaganda, ain’t that so, Doc. This one here supposed to make’em think ‘surrender and we’ll give you a shave and haircut, clean clothes, a hot meal and free ticket home.’ Sheeit!”

Kathy squinted at the tight Vietnamese calligraphy. I thought about asking Mikes’ friend Mr. Ling to translate it. Then I showed him the leaflet with the dead dink on the front and the words in Vietnamese that didn’t need explaining. Mike took one look and said, “Ain’t been dead long, probably just killed; he ain’t swelled up yet.”

I thought, ‘Jesus Christ, this fuckin guy is good, he is fuckin good.’ We could have talked for hours but Kathy was starting to nod so we called it a night and slept till mid day.

That afternoon we drove to a flea market near Frenchtown, then to a thrift store in Monroe; I began to appreciate why Jerry wanted to move to Florida.

We skipped Sears and drove to a roadside farm supply store. Mike showed me the refrigerated display case for veterinarian medicine and talked about his friend Danny.

"Yeah, he was drinking and always sick, weren’t he Kathy? Didn’t have no money or nothing.

Couldn’t afford no doctor, neither. He’d come here

cause it’s the same thing, just in bigger bottles, but the prices is cheaper;

syringes, too. Shit, he’d take that stuff home, shoot his self up, better

in no time. Kathy, you ‘member how long did that boy Danny lived ‘fore he

died? Must have been a couple of months, huh? Sheriff found him.

Dead. He’s dead alright. But didn’t need no doctor to take care his

self. No way. Ole Danny boy knew his shit, alright.”

Couldn’t afford no doctor, neither. He’d come here

cause it’s the same thing, just in bigger bottles, but the prices is cheaper;

syringes, too. Shit, he’d take that stuff home, shoot his self up, better

in no time. Kathy, you ‘member how long did that boy Danny lived ‘fore he

died? Must have been a couple of months, huh? Sheriff found him.

Dead. He’s dead alright. But didn’t need no doctor to take care his

self. No way. Ole Danny boy knew his shit, alright.”We looked at the merchandise in the horse section.

Kathy said, “Doc, this here is real good horse shampoo. It’s good for your hair. And now it’s in all them department stores, but here it’s cheaper. You can buy yourself some if you like.”

I picked out a small horse shoe instead. We browsed through the farm equipment, then headed home.

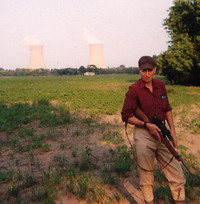

Monroe is out in the burbs, mostly middle class, and it’s gun country. Mike got a new toy for Christmas, an AR-15, the variant M-16 issued to American infantry officers during the war. We drove out to the woods, where Mike had a little firing range, taking the AR-15, a .22 caliber rifle and a .25 caliber automatic pistol.

There is nothing like the smell of cordite and the roar of bullets, the blurry smoke and the rattling gun pulsing steely tremors through your body to bring back certain memories. And the power, the unspeakable destructive power. I was plinking bottle caps using the telescopic sight, then put the 15 to my hip and peeled off a burst on semi as the civilian model can’t fire full automatic. I hate to say it but it felt good. And I knew exactly what I was doing.

The first chicom grenade had blown up the machine gun. The second blew up our position that June day in Cambodia 1970. Dorio, Larry Roy, Mike and Shake ‘n Bake all splattered with shrap, Mike getting it worst. They had thrown themselves on top of me, trying to avoid the blast, which lifted us up and threw us down. Before the head medic came over to help us out, before the gun ships power dived and rolled in, before the 155s opened up, someone sprayed the wood line with an M-16. What a rush, what a mother fuckin rush.

Mike took out the .25 automatic, cocked a sly smile, gave me a knowing look. “Here you go, Doc. Have fun with this.”

I fired a clip into a dead tree. It’s a cruel little gun. In Michigan they call it a belly buster. What petty crooks in New York City call a Saturday Night Special. Not pleasant. Not pleasant at all.

Mike got it through a gun dealer who’d bought it from the police. But there were no ID numbers so the police called them both in for questioning. Once it was clear the cops had screwed up, they told Mike to get rid of it, which he didn’t do and they knew he wouldn’t, since a good gun is a good gun, numbered or not.

We fired off another thirty rounds and it jammed twice so we put it away. It was a nasty little thing, gun country or no.

The next day the two of us went out to a corn field near a nuclear power plant to shoot ground hogs. The week before Mike had killed most of them so we walked through the tall grass as if on patrol. Mike was highly decorated; I wondered how he was dealing with war stress. We hadn’t talked much about it.