|

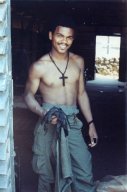

Lt. Steve Sharp 1969 |

We’re in Song Be. How long has

it been? Two weeks? Three? In

1999 the

Lieutenant said we

once spent over a hundred days straight in the bush. I said, "Are

you sure, LT?" He said, "Oh, I remember that all right." Anyway, I

give the camera to gunner

Jim Lamb, or rifleman

Jean Locklear, or point man Larry Roy, or rifleman Glenn Williams (a

handsome man later shot by Bill Williams who reflexively pulled the

trigger as he fell; an enemy round had bored into his helmet and

sliced open the back of his head. “Bill... Bill. It’s me, Doc. Bill,

you’re gonna be all right.” But his eyes are wide open and lifeless,

as if he can see everything). Or RTO

Mike Wilson who

followed

Six over the berm on

LZ Ranch, blowing the female sapper away; or brave squad leader

Jerry Bieck. I don’t remember. I loved them all. Take the picture

for Christ sake. Just take it. After the shutter clicks we have

movement, but it's a false alarm. Getting up I stuff the camera into

a waterproof bag, stuff that into my pack. Ten minutes later we move

out.

It’s the same

picture I hallucinated

in the rain forest in Sumatra while walking with Mr. Mohammed, my

guide. For three days we trek hard, morning to dusk, and I love

every mud slick minute. It’s just like the jungle in Song Be: a

great green curtain of wait-a-minute vines, dense thick scrub,

thrown down or exotic spiraling trees, the bright light filtering

through the triple layers, filling the silence with heat. In the

steam hot day we sweat buckets and march: Mr. Mohammed cuts a trail

just like Larry Roy, raising the machete's blade up, slicing it

down, whack, whack, whack. There is the returning beat of bend and

sway, of stepping or crawling under, over, or around rocks, trees or

bodies; there is the pulling of branches behind oneself so as not to

snap them or whip the man behind you. My body is hunched forward, my

trigger finger extends over an unseen trigger guard, like on patrol.

We are awash in rivers of sweat and breathing hard. The soft dirt of

the hill grows heavy and we are caked with it but when we stop we

smile. Mr. Mohammed says, “You wait here,” and goes to cut and carve

walking sticks. Without thinking

I lean forward, brace my hands

on my knees, the way we grunts did when taking five.

Beads of salty sweat roll down my face and sting my eyes but I’m too

tired to move. For no reason I look up. The life size apparition is

fifteen meters ahead. It's vivid and solid and three dimensional.

Seconds later it begins to sparkle and shimmer, then melts away.

I hear Mr. Mohammed returning. “For you,” he says, handing me a long

pointed stick. His black mustache accentuates his wide grin. I’m

drenched with my tears and the tears of my sweat so he cannot tell

I’ve been weeping. We move out.

Later, at close range we see a male orangutan and its mate, the baby

riding her back. We find a tigers lair but the animal is long gone.

Later, back at camp we see the crazy woman who lives with chickens

and ducks in her rickety hut. And later, at Mr. Mohammed's house,

his wife falls to the floor convulsing and he treats her with herbs

and incense while his toddlers play, her legs kick, her eyes roll

back, she feints and goes limp. Later, much later, after truck

rides, checkpoints, fruit bats, a rat eaten hole in my pack, visits

to the

American embassy,

visits to temples, villas, cockfights, after the blessed horseback

ride on the long white beach at

Parangtritis. After

telling the pock faced Javanese massage woman who forced her

knuckles deep into my back, “No, it's not good. 'No bagus,' ” I

said. After sitting in decrepit chairs in high domed thatched huts

in Yogyakarta's sprawling bird market, enchanted by the stink and

song and squalor. After the wretched strip malls of industrial

Surabaya; after having my fortune read by a friends sister in a six

hundred year old stone house in Beaujolais, France, “You are my

suicide man,” she said, handing me the cards. Much, much later,

after declining cocaine in London from a doctor befriended in

Mexico; after sipping red wine with friends while overlooking azure

Lake Geneva, trying my best to appear sane but knowing they knew

that I knew that I did not fool them. Later, in Amsterdam, after

visiting Rembrandt's house, Ann Frank's house, the red light

district, paying thirty guilders to a Colombian woman, “Hold me,

please hold me,” I said after we did not have sex. At last, after

hiding out in the cramped Dutch pension where I did not know who or

when or where I was: a short flight home where I arrived one day

before my DEROS twenty-six years after the event and moved sixteen

times from '96 to 2002 before finally settling down. |

Sheriff Steve Sharp 1999 |